Emigration from Silesia in the 1850s Noted historian and former professor at Wrocław University, Poland, Karol Jonca (1930-2008), explored the Silesian emigration trends in the mid-1850s: “It still cannot be determined whether or to what extent the decision to emigrate to America was influenced by information in the Wrocław press concerning the opportunities to sail from German ports. It is possible that such information reached only the emigration agents who knew German and could then use it in their emigration promotional literature. For example, the Wrocław paper Schlesische Zeitung reported that on September 15, 1854, a three-masted ship (of the so-called Bremer class) set sail for Galveston, and that on the 15th day of every month sailing ships were departing for New Orleans, New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. Moreover, on September 21 and October 12 and 19, 1854, steamships set sail for New York. “The next large group of emigrants set out for Texas on about September 20, 1854, following a major summer flood. We also know that they went by train from Gliwice to Wrocław, from there to Bremen on September 26, and from there they set sail for the Gulf of Mexico aboard the 265-ton, three-masted “Weser.” For unknown reasons part of the emigrants sailed on the brig “Antonette” a few days later, and after a long, exhausting voyage reached the port of Galveston on December 3, 1854, but sailed on to the port of Indianola (a port which no longer exists). The journey continued on foot across inhospitable prairie…” From a speech by Professor Karol Jonca, “Emigration from the Opole Region of Silesia to Texas in the Mid-19th Century” (page 14) presented at the Polish American Priests Association 10th Anniversary Convention, Menger Hotel, San Antonio, Texas, May 4, 2000.

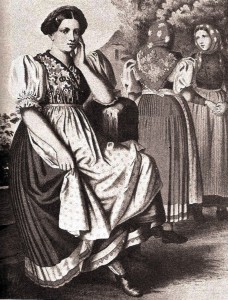

An Upper Silesian peasant girl in nineteenth century folk dress. (Illustration from Kretchmer, Deutsche Volkstrachten.) Photo from First Polish Americans, Silesian Settlements in Texas, by T. Lindsay Baker.

Appearances L.B. Russell related that as a child he had witnessed immigrants from Poland: The arrival of the colony was one of the most picturesque scenes of my boyhood. The highway between Port Lavaca and San Antonio passed directly in front of our home. Up to that time, the people of Texas were entirely English speaking but for a few colonies from Germany. The consequence of this was, that simple frontier people like ourselves have never seen anything like the crowd which passed along the road that day. There were some eight or nine hundred of them. They wore the costumes of the old country. Many of the women had what, at that time, was regarded as very short skirts, showing their limbs, two or three inches above the ankle. Some had on wooden shoes and, almost without exception, all wore broad-brimmed, low-crowned black felt hats, nothing like the hats that were worn in Texas. They also wore blue jackets of heavy woolen cloth, falling just below the waist and gathered into folds at the back with a band of the same material. From the Dallas Morning News, January 24, 1932, by G.H. Cook. Reprinted in The First Polish Colonies of America in Texas, by Rev. Edward J. Dworaczyk, 1936, Page 4 Greeting by Father Leopold Moczygemba

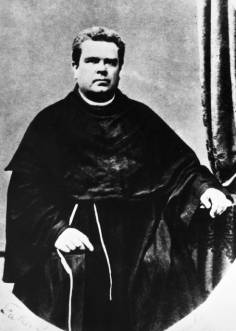

Rev. Leopold Moczygemba. Photo from Polish American Crusaders Museum, San Antonio, Texas. ITC 070-0009

Professor Karol Jonca described the Silesians finally reaching “… the town of San Antonio, where the group of 159 person was greeted on December 21, 1854, by Fr. Leopold Moczygemba, who had arrived from Castroville. If this number of persons reaching the destination is correct, then one must ask what happened to the other Silesian emigrants; the official listing indicated there were 228 of them. Surviving records provide no answer. We can only assume that exhausted by the voyage, which lasted several weeks, the emigrants did not reach San Antonio but halted along the route, or after landing along the Gulf of Mexico went in other directions. In any event, those who were greeted by Fr. Leopold Moczygemba set out with him to the southeast to the Cibolo River, where their guide had earlier acquired land, and on December 24, 1854, he celebrated Holy Mass under an oak tree there on the occasion of the Christmas Eve Wigilia. The new settlement was named Panna Maria. Part of the newcomers, perhaps disheartened by the difficult conditions—for one thing, the absence of any kind of shelter, which still had to be built—went on to the settlement of Bandera, which had been founded a bit earlier but still was under the threat of Indian attack.” From a speech by Professor Karol Jonca, “Emigration from the Opole Region of Silesia to Texas in the Mid-19th Century” (page 15) presented at the Polish American Priests Association 10th Anniversary Convention, Menger Hotel, San Antonio, Texas, May 4, 2000. Missionary Travels 1860s – 1870s

Rev. Adolf Bakanowski, O.R. Photo from Institute of Texan Cultures at UTSA, 068-1240. Loaned by John F. Dziuk Family

In 1866, a Polish Resurrectionist, Rev. Adolf Bakanowski, as Vicar-General, was entrusted with the “…organization and administration of all Polish churches in Texas.” He wrote vivid details in his Texas memoirs (1866-1870) which have been translated into English as Polish Circuit Rider: “Because of the many and varied dangers in this part of the country, which still was almost wild, we had always to equip ourselves in such a way as to insure protection of our persons. Each of us had his carbine, revolver, and hunting musket. Only in church did we wear our clerical garb, otherwise lay clothes. On journeys, especially those with horses, we looked exactly like any ordinary American traveler. Danger threatened us everywhere, from wild animals and wild people, the latter Indians….If one is obliged to travel in places where Indians are found, he generally takes along a companion or two, and all must be armed.” (page 9)

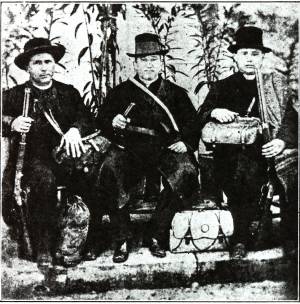

Left to right: Most Reverend John Claudius Neraz, Most Reverend Anthony Dominic Pelicier [Pellicer], first bishop of San Antonio, and Reverend Felix Zwiardowski who had been a general in the Russian army before he studied for the priesthood.

Photo from Our Polish Pioneers, un-numbered page between pages 8 and 9.